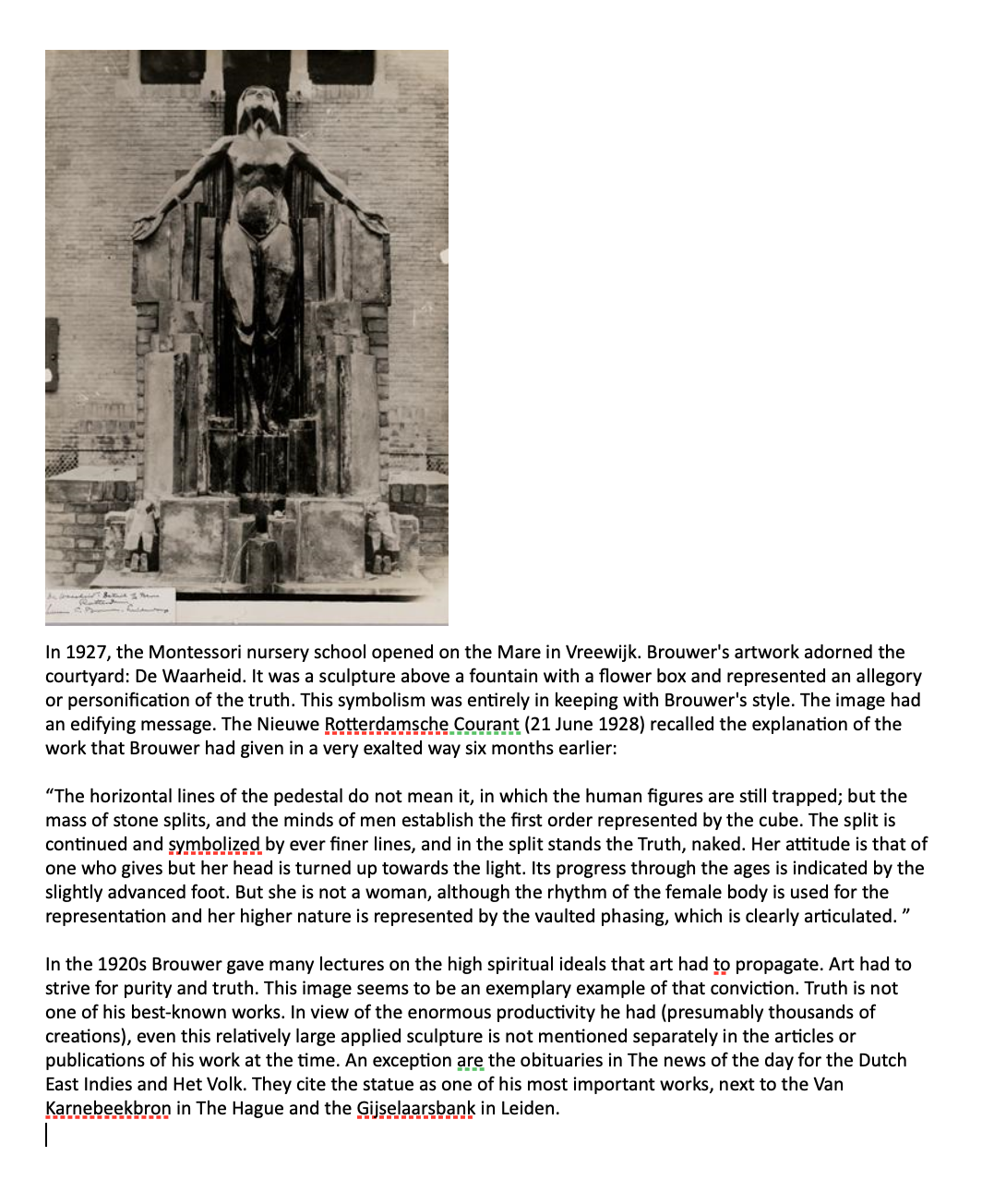

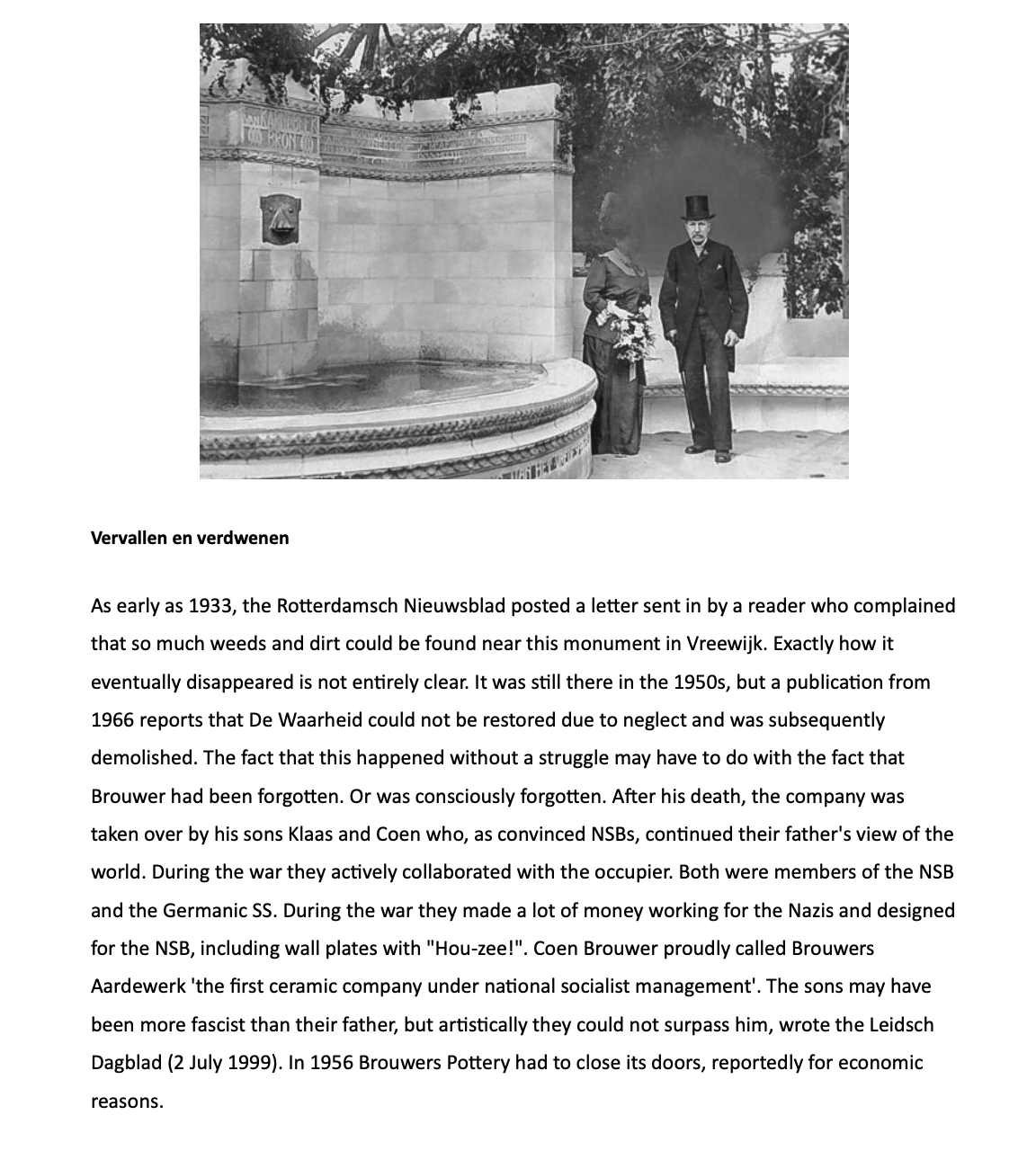

The maker’s positioning as a fascist is relevant and powerfully contrasts with the fact that the monument is called “The Truth.” This immediately brings up a question of values – what values does the statue reflect, and whose truth? The organization “100 years Vreeswijk” is planning to replace the monument with a replica in the event that they will not find it. We understand that people who are looking for the monument would like the it to return as they remembered it. However, due to the artist's fascist ideology, we do think that replacing the monument is a questionable decision and do not think it is appropriate as such. We would like to meet the people who used to visit the monument, so as to get deeper insight into the meaning of their connection with it. To value the connection that the community had with the statue, yet to create an intervention that would oppose the supremacy imposed by its fascist roots, our idea was to make it accessible to everyone from Vreewijk by building a different kind of truth – one that allows the people of the community to tell their stories and share the meaning that the statue has for them, which would be interactive, virtual and filled it with stories from the people of Vreewijk.

The final result would consist of a digital intervention accessible with a QR code – when someone would pass by the place in which the statue used to be, the app or website would show the statue, in a state of invisibility – but becoming gradually visible by being filled up with the stories of the Vreewijk community.

The following feedback session was centered around making the project sustainable and continuing to work on it after the deadline. We decided to use the original shape of the monument in respect for the people of Vreewijk’s wish to have the monument back – however, creating the possibility for people to add stories to the ever-growing monument. By becoming interactive it becomes inclusive. We want the stories to live on and by that bring the past to the future, as inspired by Laurenskerk.

Our next step was looking into archives to find more about the statue, as there was little to no information available online. We decided to contact people that could tell us more – specifically, Peter Klerk from “100 Jaar Vreewijk”, Julia from “Vreewijk Havensteder”, Siebe Thissen from “BKOR/CBK Rotterdam”, Pieter, Han van Dam from “Wijkmanager”, and Joshua Van Den Ham from “Tuindorp Vreewijkcooperatie U.A.” We found out that there are several people from Vreewijk who are looking for the statue. The organization called “100 years Vreeswijk” has assisted these people in their search for the monument.

Our process took place on 3 parallel levels. The first part was the concrete research: talking to people from the community and digging up history and information. This shaped the second part, namely the conceptual research, while the third part consisted of the artist strategies which would be used to create the final result.

In parallel, we looked for inspiration from artist strategies. One technique that stood out was the interactive way in which a “LGBTQ” monument in New York connected people of the community through shared memories. We decided to combine this interactive community initiative with the St. Laurence Church’s technique of blending past and present in a virtual, audio-visual intervention in the shape of a public website.